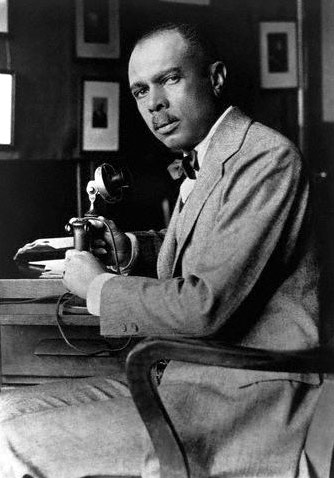

Biography of James Weldon Johnson

Sunday, March 27, 2011 at 11:22AM

Sunday, March 27, 2011 at 11:22AM

Songwriter, poet, novelist, journalist, critic, and autobiographer. James Weldon Johnson, much like his contemporary W. E. B. Du Bois, was a man who bridged several historical and literary trends. Born in 1871, during the optimism of the Reconstruction period, in Jacksonville, Florida, Johnson was imbued with an eclectic set of talents. Over the course of his sixty-seven years, Johnson was the first African American admitted to the Florida bar since the end of Reconstruction; the co-composer (with his brother John Rosamond) of 'Lift Every Voice and Sing,' the song that would later become known as the Negro National Anthem; field secretary in the NAACP; journalist; publisher; diplomat; educator; translator; librettist; anthologist; and English professor; in addition to being a well-known poet and novelist and one of the prime movers of the Harlem Renaissance.

As the first son of James Johnson and the former Helen Louise Dillet, James Weldon inherited his forebears' combination of industrious energy and public-mindedness, as demonstrated by his maternal grandfathers long life in public service in the Bahamas, where he served in the House of Assembly for thirty years. James, Sr., spent many years as the headwaiter of the St. James Hotel in Jacksonville, Florida, where he had moved the family after his sponge fishing and dray businesses were ruined by a hurricane that hit the Bahamas in 1866. James, Jr., was born and educated in Jacksonville, first by his mother, who taught for many years in the public schools, and later by James C. Walter, the well-educated but stern principal of the Stanton School. Graduating at the age of sixteen, Johnson enrolled in Atlanta University, from which be graduated in 1894. After graduation, Johnson, though only twenty-three, returned to the Stanton School to become its principal.

In 1895, Johnson founded the Daily American, a newspaper devoted to reporting on issues pertinent to the black community. Though the paper only lasted a year (with Johnson doing most of the work himself for eight of those months) before it succumbed to financial hardship, it addressed racial injustice and, in keeping with Johnson's upbringing, asserted a self-help philosophy that echoed Booker T. Washington. Of the demise of the paper he wrote in his autobiography, Along This Way, "The failure of the Daily American was my first taste of defeat in public life. . . ." However the effort was not a total failure, for both Washington and his main rival, W. E. B. Du Bois, became aware of Johnson through his journalistic efforts, leading to opportunities in later years.

Turning to the study of law, Johnson studied with a young, white lawyer named Thomas A. Ledwith. But despite the fact that he built up a successful law practice in Jacksonville, Johnson soon tired of the law (his practice had been conducted concurrently with his duties as principal of the Stanton School). When his brother returned to Jacksonville after graduating from the New England Conservatory of Music in 1897, James's poems provided the lyrics for Rosamond's early songs. By the end of the decade, both brothers were in New York, providing compositions to Broadway musicals. There they met Bob Cole, whom Johnson described as a man of such immense talent that he could "write a play, stage it, and play a part."

The brothers split their time between Jacksonville and New York for a number of years before settling in New York for good. However, their greatest composition, the one for which they are best known, was written for a Stanton School celebration of Lincoln's birthday. "Lift Every Voice and Sing" was a song that, as Johnson put it, the brothers let pass out of [their] minds," after it had been published.

But the song’s importance grew from the students, who remembered it and taught it to other students throughout the South, until some twenty years later it was adopted by the NAACP as the "Negro National Hymn."

It was this kind of creativity under duress, coupled with his connections in the political sphere, that characterized Johnson's life as an artist and activist. Indeed, between the years 1914 and 1931, his desire to explore the limits of both worlds led him to seek a more thorough synthesis of his public and artistic sensibilities. The study of literature, which Johnson began around 1904 under the tutelage of the critic and novelist Brander Matthews, who was then teaching at Columbia University, caused Johnson to withdraw from the Cole/Johnson partnership to pursue a life as a writer. However, this creative impulse coincided with his decision in 1906 to serve as United States consul to Venezuela, a post that Washington's political connections with the Roosevelt administration helped to secure.

During the three years he held this post, Johnson completed his only novel, The Autobiography of an Ex-Colored Man, which he published anonymously in 1912. Though many read the novel as a sociological document, its true value lies in the manner in which it recasts the "tragic mulatto" story within the context of Du Bois's metaphor of the veil. The novel sparked renewed interest when Johnson announced in 1927 that he had authored the book as fiction. Indeed, so great was the public propensity to equate the novel's hero with Johnson himself that Johnson felt obliged to write his autobiography, which appeared in 1933 under the title Along This Way.

He had, by this time, established himself as an important figure in the Harlem Renaissance. From his post as field secretary of the NAACP, Johnson was a witness to the changes taking place in the artistic sphere. As a prominent voice in the literary debates of the day, Johnson undertook the task of editing The Book of American Negro Poetry (1922), The Book of American Negro Spirituals (1925), TheSecond Book of American Negro Spirituals (1926), and writing his survey of African American cultural contributions to the New York artistic scene in Black Manhattan (1930). His own career as a poet reached its culmination in God’s Trombones, Seven Negro Sermons in Verse, published in 1927. Though not noted for playing the role of polemicist, through each of these literary enterprises Johnson worked to refute biased commentary from white critics while prodding African American writers toward a more ambitious vision of literary endeavor. It was Johnson's great hope that the contributions of younger writers would do for African Americans, "what [John Millington] Synge did for the Irish," namely utilizing folk materials to "express the racial spirit [of African Americans] from within, rather than [through] symbols from without. . . ." Hence Johnson's attempt to discredit Negro dialect, a literary convention characterized by misspellings and malapropisms, which in Johnson's view was capable of conveying only pathos or humor. Though writers like Zora Neale Hurston and Sterling A. Brown would challenge this viewpoint, Johnson's point must be understood within the context of his life as a public figure.

With the arrival of the 1930s, Johnson had seen the NAACP’s membership rolls and political influence increase, though the latter failed to produce tangible legislative and social reform in Washington. Retiring to a life as Professor of Creative Literature and Writing at Fisk University, Johnson lectured widely on the topics of racial advancement and civil rights, while completing Negro Americans, What Now?(1934), a book that argued for the merits of racial integration and cooperation, and his last major verse collection, Saint Peter Relates an Incident: Selected Poems (1934). Though he died in a tragic automobile accident while vacationing in Maine in June of 1938, Johnson continues to be remembered for his unflappable integrity and his devotion to human service.

Reader Comments